listening to place.

- Lottie Anne Murray

- Dec 16, 2025

- 4 min read

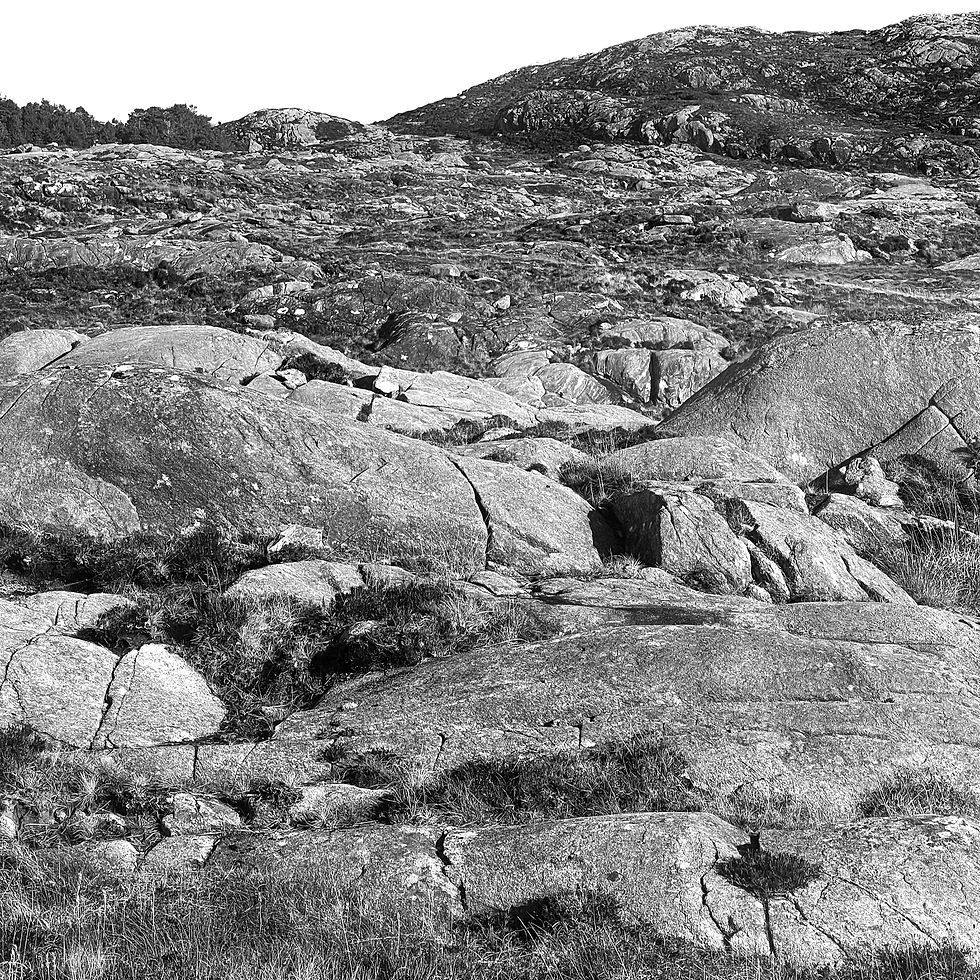

Much of my writing has focused on reading loss, absence, and marginality in the Hebrides. This post asks a different question: what does it look like when architecture responds well to that knowledge? Caochan na Creige listens and answers.

With Caochan na Creige recently named RIBA House of the Year 2025, its recognition offers a timely moment to reflect on how small, locally rooted projects can articulate broader architectural values. For me, this reflection sits closely alongside my recent dissertation and previous blog posts on the Outer Hebrides, where I examined how architecture at the so‑called “edge”, often treated as peripheral in discourse rather than geography, becomes a register of land, memory, and cultural continuity. The qualities for which the project has been celebrated — sensitivity to land, material intelligence, and collective authorship — mirror those identified throughout this research as markers of enduring and meaningful architecture. Its success signals not an exception, it points toward the potential for many more successes to emerge from rural regions when design is allowed to grow from place rather than be imposed upon it.

Too often, rural architecture is discussed as a singular category: remote, marginal, or constrained. Yet my research repeatedly demonstrated the opposite. Rural places are not empty backdrops but deeply storied landscapes, shaped by long histories of settlement, displacement, adaptation, and care. Architecture in these contexts does not simply respond to climate or material availability; it negotiates identity. It carries traces of language, land tenure, and ways of living and makes visible how these forces continue to shape contemporary decision-making. Small buildings, in particular, reveal this most clearly.

Their scale demands restraint. Their success relies less on spectacle and more on attentiveness — to landform, to weather, to how people inhabit space over time. In my dissertation, a comparative analysis of dwellings; from blackhouse ruins to contemporary homes, revealed that the most resonant architecture was not defined by stylistic reference, but by continuity of thought. These projects worked because they were grounded in local logics of building: repair over replacement, adaptation over imposition, and respect for the land as an active collaborator.

[kinship.]

Equally important is the way such buildings come into being. The self-build process recalls older Gaelic kinship traditions, where the making of a home was not an individual act but a communal one, shaped through shared labour, reciprocity, and inherited knowledge. Concepts such as dùthchas instil a sense of belonging rooted in collective responsibility to land and community, framing building not as ownership alone, but as stewardship across generations.

Architecture becomes a continuation of language and culture, enacted materially through participation rather than consumption.

Local materials and makers are therefore not simply specified, but involved. Craft, memory, and care are embedded in the fabric of the building through relationships, between families, neighbours, and landscape. Against the growing dominance of imported housing systems, which often arrive detached from local skill or story, this approach offers a quieter alternative. It reflects a way of building that remains socially inclusive and culturally grounded, where making is itself a form of belonging, and where architecture holds space for the persistence of language, kinship, and place.

[understanding of place.]

Caochan na Creige exemplifies this condition. Its achievement lies not in novelty, but in clarity: a deep understanding of place translated into a contemporary architectural language. The project demonstrates how working closely with landscape, material, and cultural context can result in architecture that feels both specific and enduring. It is a reminder that innovation does not require detachment from tradition — often, it requires deeper engagement with it.

This observation resonates strongly with the central argument of my research: that architecture at the edge is not peripheral to architectural discourse, but essential to it. Regions long shaped by constraint have developed sophisticated spatial and material intelligence. These places understand limits; environmental, economic, social, and within those limits have cultivated forms of ingenuity that are increasingly relevant today, particularly in the face of climate uncertainty and resource scarcity.

Vernaculars were never stylistic choices, but responses to necessity and locality; to build meaningfully today is to rediscover these logics, not imitate their appearance.

What emerges is not a call for replication, but for listening. Rural architecture cannot be approached with an ‘apply‑to‑all’ mindset. Each region holds its own dialogue, shaped by different ecologies, histories, and social structures. To design well within these contexts requires time, humility, and an acceptance that the architect is not the sole author, but part of a wider continuum of making.

[belonging to the land.]

The success of small, locally rooted projects challenges dominant assumptions about value in architecture. It suggests that meaningful impact is not measured by scale or visibility, but by depth of connection, to place, to people and to processes of making that unfold over time. When architecture is allowed to grow from the land — materially, culturally, and socially — it gains a quiet resilience. It belongs.

It is worth acknowledging the collective labour behind such work, family members, local makers, and craftspeople, whose contributions are integral to architecture that genuinely belongs, and who demonstrate how Hebridean values of kinship and craft can still meaningfully shape contemporary design.

For me, this moment feels less like an endpoint and more like confirmation, allowing for learning from the edge. The themes that shaped my dissertation — land, loss, continuity, and authorship — are not abstract concerns, but active forces in contemporary practice. Projects such as Caochan na Creige demonstrate that architecture which listens carefully to place can resonate far beyond its immediate context.

At the edge, architecture often speaks softly. But when we take the time to listen, it has much to teach us about how to build futures that are grounded, generous, and true to the landscapes we inhabit.

[for further readings and understandings of topics touched on in this post please read my other posts.]

Comments